Automated Bounding Boxes

When it comes to computer vision, it’s extremely helpful to have a large sample size of nicely labeled data. A problem arises when you’re neither a big tech company with ample resources nor can you benefit from labeled crowd sourced images from places like open images

So what’s a resourceless group of students supposed to do in this case?

Inspiration

I’m currently working on building a recycling app with some fellow data scientists, some web developers and a few UX/UI designers which you can checkout here:

In this project, we want to make recycling extremely easy for a user. The app is in the current state, an interface connecting the user to database of recycling information. Information that’s local (as regulations vary at even the city level). However, we want to make things as easy as possible on the user, they need only point the camera and click to get relevant recycling information (rather than navigating a click funnel maze for the item they want to recycle, though that option is available as well as a search bar).

The problem was getting enough labeled images to train our computer vision model and that’s what this blog posts seeks to address.

A simple idea

You’ve likely used Google, Bing or some other search engine and clicked on the images tab. You may have gone further and discovered there’s an “Advanced Settings” from which you can specify all sorts of parameters:

- size

- region

- aspect ratio

- color

- transparency

It’s this last one which is relevant here. Selecting transparent images will return usually PNG files (sometimes GIF). These are often images someone or some company (or some … thing o_0) removed the background with things like Photoshop for nice product placement (presumably to be friendly for dark mode).

These images are absolute gold! I wrote a fairly straightforward script that went along each edge of the image until it hit a non-transparent pixel. For more information, PNG images are represented with 2x2x4 matrix, 2x2 for the height and width, the depth of 4 specifies it’s Red, Green, Blue and Alpha components. Alpha here is the transparency which takes on a value between 0 and 255. 0 means that pixel fully transparent, 255 means that pixel is fully opaque.

Initially I just summed each row until a non-zero sum was reached, and that was ok when the images had hard stopped edges, but more professional images usually have a degree of shading, so I changed it to only stop the pixel counting if the row was non-zero AND a value of 255 was present in that row and so far, it’s been working great. The following image should make that progress clear.

Other concerns

Duplicate Images?

Yeah, that can be a problem, so I thought we should simply rename the downloaded images to the their md5sum hash. It’s not perfect because hashes aren’t one-to-one or reversible, but 32 characters long from a sample of 16 (i.e. 16^32) is a lot and the chance of an overlap is practically zero. But don’t take my word for it, let’s justify with some math. Taking into consideration the “Birthday Paradox” and using Stirling’s approximation, I arrived at this as the probability that any image will share an md5sum with any other:

\[\frac{n!}{n^q(n-q)!} \stackrel{\text{Stirling}}{\approx} \frac{\sqrt{2\pi n}\left(\frac{n}{e}\right)^n} {n^q \sqrt{2\pi (n-q)} \left(\frac{n-q}{e}\right)^{n-q}} = \left( 1-\frac{q}{n} \right)^{q - n - 1/2}\]Here, n is the total number of unique md5sum hashes, all 10^31 of them, q is the number of images we have. A decent sample size is ~2000 for every class. We will have about 400. (Assume q = 2000 x 400 because there’s about 400 recyclable items in the database)

This converges to 1 (so the probability that any image will share the same md5sum is 1 minus that … effectively zero. Intuition:

\[(1 - \text{a really small number}) ^ {\text {(a really large negative number but it doesn't matter because the base is 1)}}\](Note: yeah, I know the derivation of Euler’s number is similar, 1 + small number to the power of a big number, but that’s not the case here, I triple checked)

The script to resize and rename the images, checking for duplicates was done by Vera.

In order to not over fit to images with blank backgrounds (or whatever the default may be, white or black), a simple script that randomly appends sensible backgrounds to the object class was written by Tim Hsu. (He also modified an existing script to gather images from Bing that suits our needs very well)

But what about non-png files?

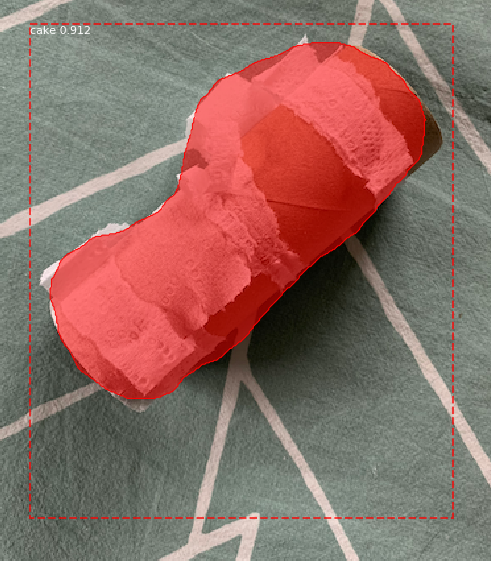

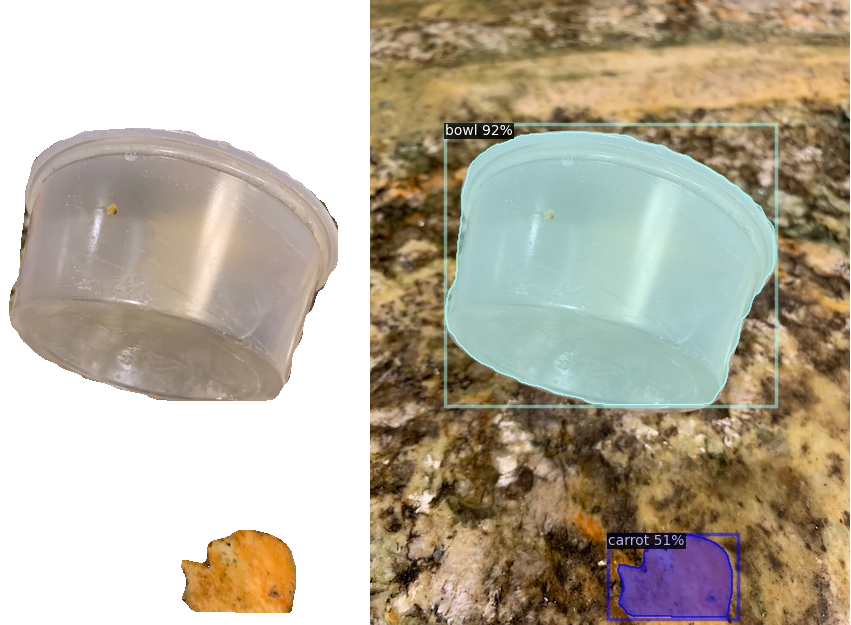

Great question. And to this I direct you to another one of my very smart project-mates Tobias. In a clever way, he used Facebook’s Detectron2 which is itself software used for image segmentation. At first that sounds paradoxical: if we can segment the image, aren’t we already able to identify it? Well if you take some shortcuts and just train it semi-poorly, it will quickly be able to detect the foreground of an image with the hilarious side effect of labeling it wrong, but that’s ok, we don’t need accurate labels at this point. Checkout his script here.

|

|---|

| Not exactly the kind of cake I would eat |

|

|---|

| Does kinda look like a carrot… |

In summary, this object Detectron2 is an object recognition model, and out of the box, it can find the foreground for objects similar in shape to what it has been trained on. Tobias figured we could lump together some samples of our training data, enough to allow it to recognize the general shape, separating them from the background. Everything else works more or less the same, we separate the background, save as a separate png, use that to find the coordinates of the bounding box (except we don’t need to append a background, we just keep the existing one)

Data Pipeline

All this has been grouped into a single pipeline. Once we have enough images downloaded and vetted for each of the classes we’re making, we just run it through and watch the training data. There’s likely gonna be some issues with some of the bounding boxes. And while I’ve already written a script to quickly view the bounding boxes, I need to implement something to speed up any corrections to the bounding box coordinates if need be.

This is an ongoing project and I’m very excited by what we’ve been able to accomplish as far as laying down the framework for the pipeline. I haven’t even mentioned the front end team and amazing work done by the UI/UX designers. A more official shoutout is due in the next post about this. Until then, I’ve gotta keep downloading images.