Crossfit Webscraping

The following is the explanation of a program I wrote. The completed project and write-up can be found here.

Non-standard library needed:

Selenium - pip3 install python3-selenium

Beautiful Soup - pip3 install python3-bs4

Inspiration

I used to do Crossfit. I was stationed in New York state for post-bootcamp training and we were provided access to the local YMCA. I took advantage of the free membership and followed the 2-days-on-1-day-off regimen as RX’d by the main Crossfit website. I did this for about a year and a half, but it got hard to be consistent when I transferred to a ship. At the time you would log your workouts in the comment section of the post, so I could go back to any date and search my name.

I still exercise now, usually it’s more oriented towards training for climbing and everything I do, I log in a free google-provided blogging platform (blogger). I had always wanted to go back and grab off my posts for my own records and add them to my blogger record just in case they were to get archived or something I would have my own copy. The problem is they are spread over a year and a half and it would be an entire day’s work to do find them all, perhaps even longer because I don’t remember exactly my start and end date so I would be searching probably over a 3 year span just to be safe.

One day I realized I could automate this searching and that’s where this program comes in.

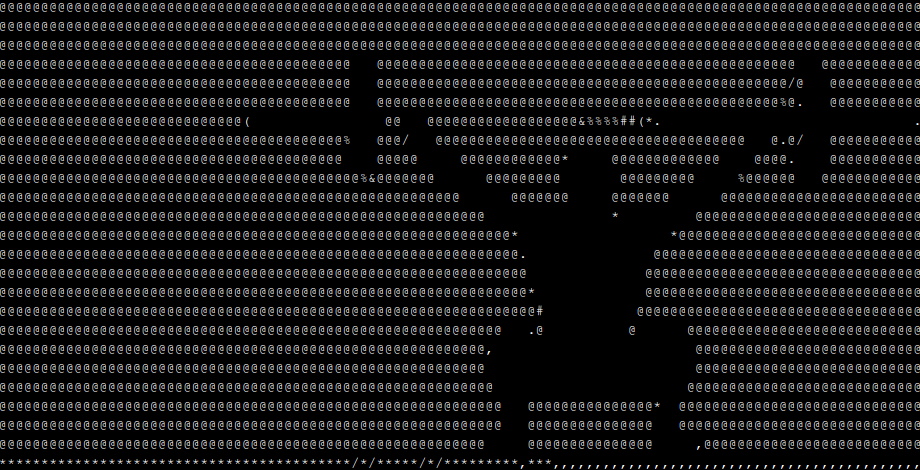

At the end of it all, here is the final result:

Code Overview

The libraries are quite nice. Beautiful Soup is… well, a beautiful library that will allow for easy parsing of HTML. It will first make a “soup” (actually it makes a parse tree as opposed to a “tag soup” as other HTML parsers do, hence the name “beautiful soup”) of the webpage you’re loading then it will allow you to search it by the tags, attributes, or combinations thereof. You could certainly do this using regular expressions (re is the de facto regex python library), but this can be tedious.

I glanced and found the description of the “workout of the day” (WOD) is always in a <p> tag within a <div> tag with the class “content”. There are sometimes multiple paragraphs describing the workout, but it would always have a paragraph instructing the users what to post in the comment, whether it was total rounds, weights, time, etc. It would always begin with the word “Post”. e.g. “Post time and weights in the comments”. I didn’t want to include that personally in my parsing because it should be understood through context, and I didn’t want any of the other “junk” in those post paragraphs (usually a quote, or link to an instructional video/article” so I ignored that line and any that followed. I took all this into account with the following:

WOD = soup.find("div",{"class":'content'})

WODdescription = WOD.find_all('p')

for i in range(len(WODdescription)):

line = WODdescription[i].text

if line.split(' ')[0]=='Post':

break

else:

print(line)

Now, sometimes I would have multiple posts in the same day. I wanted them. I also didn’t necessarily know if my first post was gonna be my WOD results, I could have asked a clarifying question or commented or said something douchy like “Bro! can’t wait to get wrecked by this WOD later this afternoon” (I don’t recall ever being that pompous, but we never really can know our 19-year-old selves). Regardless, to ensure I got all my posts, I would scour each instance of my user name and corresponding paragraph

You see, from what I’ve seen, the HTML has a <div class=name> followed by a <div class=text>. After looking at several pages, I’ve noticed these class doesn’t get used prior to the user comments, so I’m making the very strong assumption that this is the case for all posts (it probably is though… not that I’m pompous or anything)

This would all be great and complete if everything was stored purely in HTML, but just loading the HTML for the page isn’t enough to access the comments. Usually JavaScript loads that from a database. We can see this is true if we examine /assets/build/mustache/mustache.js and assets/build/comments.js, it becomes apparent this is the case. So we need a browser to open the page to allow the JavaScript to load comments so they become searchable, this is where Selenium comes in.

To use Selenium, you need to download a driver. I use google-chrome because of arbitrary familiarity.

Insights Gained

Loading Failures

I originally ran the script and would get mixed results; sometimes the page would recognize my username, and sometimes it wouldn’t. I attempted to fix this by importing time and using time.wait. I figured it just needed more time to load the page. That helped a bit, but it wasn’t perfect. The fault is actually with Selenium, it’s not perfect and sometimes the webpage just won’t load. I’m not sure why it happens more often here than with a traditional browser, but I fixed this by adding a waitForLoad() function that operates on the browser

def waitForLoad(browser):

try:

WebDriverWait(browser, 10, ignored_exceptions=[

NoSuchElementException, TimeoutException

]).until(EC.presence_of_element_located((By.CLASS_NAME,'name')))

except TimeoutException:

print("Error, timed out, trying again")

browser.refresh()

waitForLoad(browser)

return

The purpose of this is almost completely inferable by examining the English, but I’ll explain: This will delay the rest of the program from running until the expected condition of getting an element with the class “name” occurs (i.e. our usernames). It gives the program a specified time to wait, 10 seconds in this case, and if that timeout exception occurs, it will refresh the browser and again wait for it to load.

Displaying and Saving results simultaneously

Since my main purpose of this was to get a text file with this output, I needed to write the results to an external file. I also wanted everything to be displayed as it is being produced, because it sucks to have to wait until the script is finished before seeing any output on your terminal. Normally I would invoke os.system(command) where the command would append the results to an external file. But the unknown presence of newlines and quotes made this a little tough, so I decided to use the Linux utility tee which will write to std output and to an output file. So it’s a bit unfortunate, I like things to be as simple as possible without requiring the user to specify arguments, however in this case it’s just gonna have to be a little less simple. The program runs with:

crossfit.py | tee output_file.txt

This is very simple, but it comes with one last snag… it still waits until after the script is complete to write to std out!! Fortunately the fix is easy. As it turns out, python’s standard output is buffered, so it stores everything until the program ends, unless we “flush” the buffer. That is achieved simply using sys.stdout.flush()

Easy day.